Art of Simulation, Simulation in Healthcare

7 tips for healthcare simulation success from Johns Hopkins

Curious about how healthcare organizations are enhancing performance worldwide? Simul8 is enabling healthcare organizations around the world to improve levels of performance using often limited resources and budgets. But what are the factors that you should consider when launching and growing successful performance improvement programs with discrete event simulation (DES) software?

After producing an in-depth case study on how Simul8 helped slash emergency department length of stay by 16% and reduce average wait times from 61.8 to 16.2 minutes at Howard County Hospital, we sat down with Howard County General Hospital Innovation and Continuous Improvement Facilitator, Eric Hamrock.

Eric shares his recommendations through his own experience of delivering operational leadership, performance improvement, and project management for Johns Hopkins Health System.

1. Start with a project champion

I think the first and most important thing when I get into a process improvement project, especially a simulation project, is that we have a strong project champion. Having a clear champion who can give us a direction of where we want to go is what really enables the team at Johns Hopkins to be successful.

For example, our Chief Administrative Officer, Jim Scheulen, is someone who has really championed the use of simulation for us. For a long time simulation had been primarily used in manufacturing and other industries, but Jim was really at the forefront of bringing simulation in to a healthcare organization like Johns Hopkins, he wanted to deliver value based care.

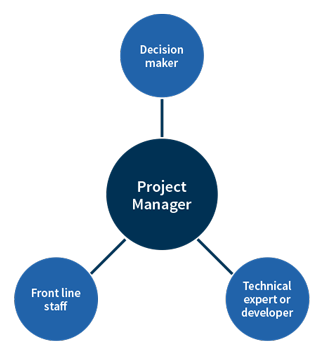

Similarly, it is important that we have a Project Manager and decision-maker guiding the group and allowing them to know what it is that is expected; what does success of the simulation entail? The Project Manager can act as an interpreter between the key stakeholders and can play an important role in ensuring that the appropriate data is collected.

But what if you don’t have this champion within your organization? I have found that if you can show successes in smaller areas of your organization using simulation, and evangelise this, that can help.

I do sometimes wish I had a magic wand to just turn stakeholders to see the benefits of it, but I think it is essentially about educating, convincing, and selling results.

2. Define a clear project scope with desired outcomes

It is very important that we define our project scope up front. Anybody who has been involved in project management knows the pitfalls of scope creep!

It’s not a bad thing if we want to start asking different questions, but we need to be clear about the key question up front, and that our project is really focused on that.

As we discover different things, then we can increase learning through further projects, or perhaps increase the project scope in a methodical way.

3. Assess sources of quality data

It is really important to understand what data we have available and where that data can be gleaned from.

Fortunately, many health systems and important companies such as Functional Medicine Associates are now using electronic systems that allow us to easily access data on the fly and even on a real-time basis. Although this hasn’t always been the case with previous projects that I have worked on, so some manual collection of data may have to be undertaken.

Quality is important, but if there is a lack of accurate data, this doesn’t mean we can’t start testing the simulation, we just have to prepare contingency plans and processes to get that data in place down the line.

4. Involve stakeholders early

We always try to involve stakeholders on a simulation project. If we assume we know what the process is and we don’t ask the people that are actually doing it, the simulation model could look very different than what the reality is.

It’s important in any project that we understand the problems that the people who are involved in the process are facing; besides that, when we include them from the start, we are more likely to be successful when changes highlighted by the simulation are proposed. If front line staff are bought into the simulation and have helped design it, it’s more likely to catch on.

I would also recommend educating stakeholders about discrete event simulation and what the possibilities are. This helps them to think about organizational problems and understand how simulation could be used in different scenarios to help decision making and improve processes.

5. Map out your processes

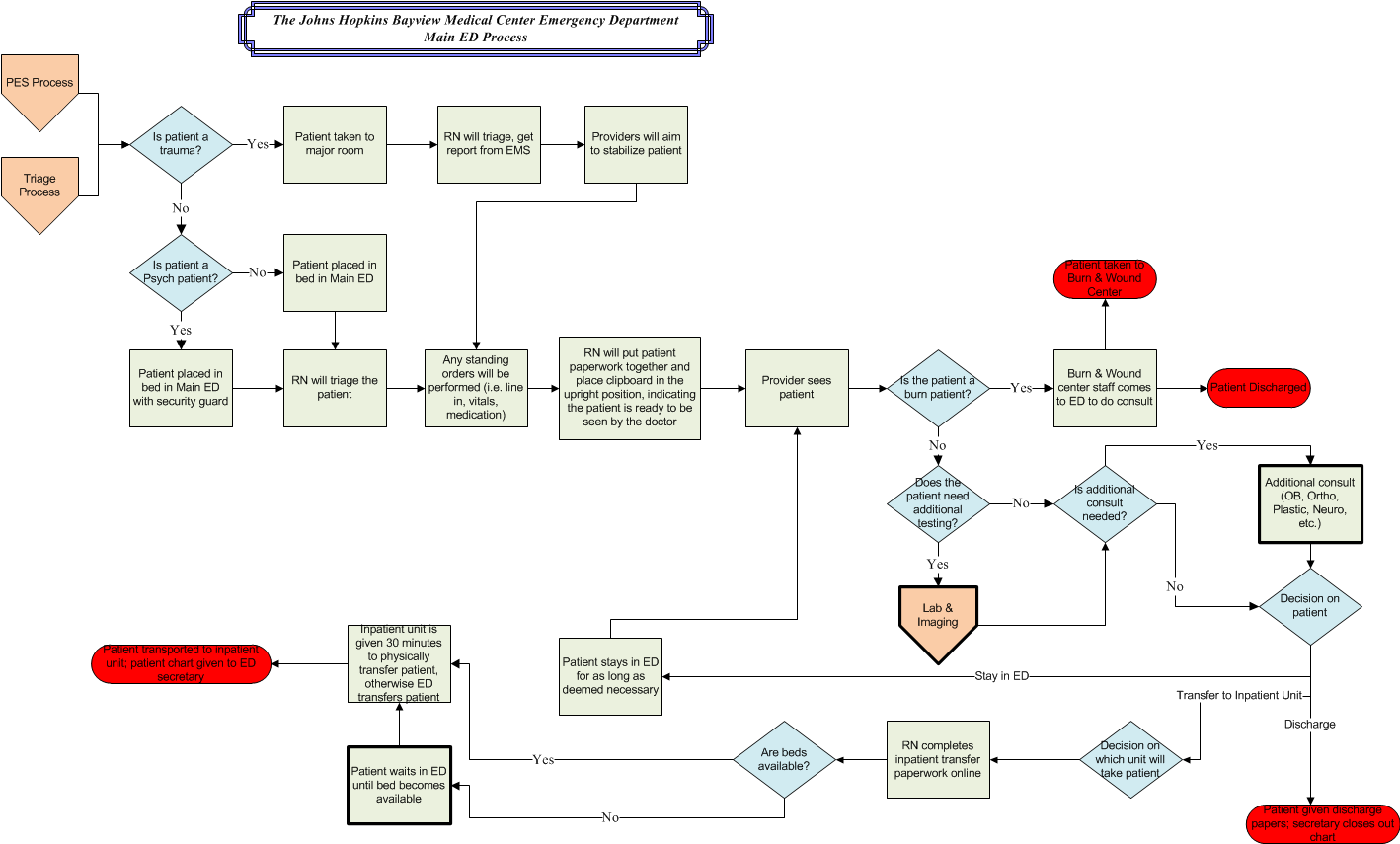

It’s important that we map the process out and to ensure we are covering all of these in the simulation. You can see a typical process map example from John’s Hopkins Bayview facility model here.

The pentagons at the beginning of the process are arrivals, the diamonds are decision points; in our model, this indicates the queues or wait times that occur. The blocks are work process areas where we are handling work, and the oblong ovals are the end of the process, when we have completed the work.

6. Phase your simulation and make iterative changes

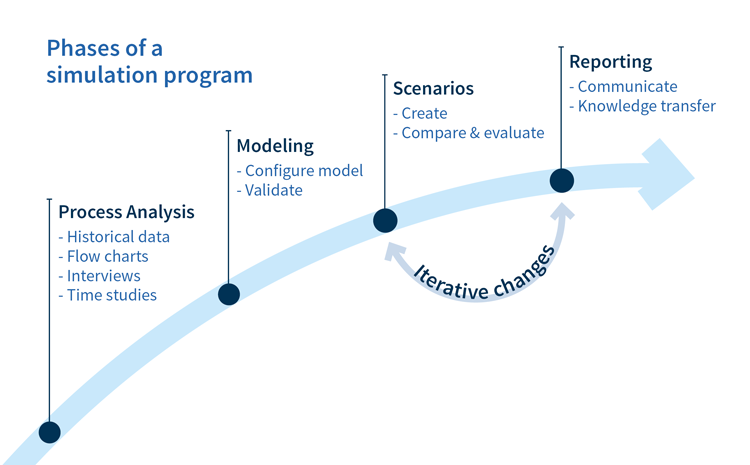

Step 1: Process analysis

Firstly, let’s analyze the process, look at historical data and understand what is really going on. How does the process work and what are those discrete events that we need to identify and capture to be able to build the simulation model?

This piece of the process tends to take up the majority of the project and it’s where we learn a lot. It’s about understanding what our current state is gives us the base to look to the future.

Step 2: Modeling

The modeling stage is next, this where we configure our process model, build the simulation in Simul8 and then validate that it is representative of real world conditions.

Step 3: Scenarios

We then create scenarios where we look at the different things that we want to test. For example, if we add six major care beds to this emergency department, what will that do for us? If we increase staffing on the night shift, what will that do for us as far as throughput, as far as wait time, etc?

Step 4: Reporting and making iterative changes

Once we have built the scenarios, we will run our simulation and report the findings back. What normally happens is that we will use this information to inform us on which questions to ask next.

We will do many iterations of this, going back to add further scenarios, tweaking these and seeing what those outputs are.

7. Start simple and grow from there

In summary, as far as lessons we have learned at Johns Hopkins Health System, I recommend starting simple and building from there.

Simulation model building can provide enormous value just by starting to get your team to think through all the aspects of your processes. The discussions that we had to have, and the explorations that had to go on in order to build our simulation models often went a long way towards illuminating how to best improve them.

If you have multiple emergency departments in your system, or even if you think you are going to be using the models over and over again, we have learned that it is very useful to take the time to build a robust, easy to use interface. You will find that it not only makes it faster to run simulation models, but it also makes it so that you can turn simulations around more quickly.

And finally, I want to emphasize the point that it is okay to start with less than perfect data; just understand, validate the model enough to know how far you can trust the results of the model. There are some simulation models where we have said, ‘Well, we cannot get it to validate perfectly,’ usually because there is some part of the process that is too complex or the data is not available, but we can still use that as a base.

Looking at such simulation results, even with placeholder data, will still provide a stronger base for decision making than throwing your hands up in the air and saying, ‘I’m just going to guess that this is what the outcome will be’!